13 October 2025

The Race Against Spoilage: The Case for Passive Cooling in Guinea-Bissau

The Postharvest Challenge

Agriculture is the lifeblood of Guinea-Bissau, with eight out of ten citizens depending on the land for their survival and income. While cashew nuts and rice dominate the landscape as the primary cash and sustenance crops, the production of fruits and vegetables, largely led by smallholders and female farmers, serves as the critical frontline for the country’s nutritional security. These horticultural activities, focused on crops like onions, okra, tomatoes, and peppers, are essential for combatting widespread malnourishment and improving diet quality. However, farmers remain acutely vulnerable to environmental volatility, relying on traditional practices in a landscape where the absence of modern infrastructure and irrigation turns every harvest into a high-stakes race against spoilage.

The reality of production is strictly dictated by the seasonal cycle and the competing demands of the agricultural calendar. While vegetables can theoretically grow year-round, the labour force shifts heavily toward the cashew harvest from March to June, leaving horticulture neglected just as the dry season reaches its peak. This labour competition, combined with limited water availability outside the rainy season, leads to a “lean season” – a period of severe shortage for fruits and vegetables between June and October. Frequent extreme weather events further intensify the situation, accelerating crop spoilage and making ambient storage unfeasible.

During these months, Guinea-Bissau is forced to import staples like tomatoes and onions from neighbouring Senegal and Guinea-Conakry, often at high prices that strain household budgets and deepen the economic vulnerability of rural communities. The situation is fundamentally paradoxical: the country suffers from food scarcity during the rainy season not because of a lack of fertile land, but because it cannot preserve the abundance of the preceding months.

Addressing this storage deficit through passive cooling technologies offers a strategic path forward. By focusing on the dry season, when environmental conditions like low relative humidity allow evaporative cooling to function at its highest efficiency, the country can better maintain the quality of its fresh produce. Implementing these low-cost preservation methods allows the hard work of Bissau-Guinean farmers to translate into extended shelf life, primarily securing household consumption for longer periods. Furthermore, this cooling capacity offers the possibility of market leverage, providing farmers the option to wait for better prices rather than being forced into immediate sales. While passive cooling is a short-term solution that cannot fully bridge the lean season, it provides a vital bridge that supports both family nutrition and potential economic gain.

While the BASE Foundation and Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology (Empa), through funding from BMZ in cooperation with ECOWAS, introduced four active cooling rooms in Guinea-Bissau in Bafatá, Gabú, Bolama, and Quinara under the Fund for Regional Stabilisation and Development in Fragile Regions within ECOWAS (FRSD) managed by GIZ, they also conducted experiments to test the viability of passive cooling solutions for household level storage. Furthermore, we conducted intensive training on community-led passive cooling across the four regions to allow for shelf-life extension options to be available even in cases when active cooling was not possible due to financial, geographical, or other constraints.

Closing the Infrastructure Gap with Passive Cooling

In Guinea-Bissau, the most heat-sensitive crops are those central to the horticultural sector, including highly perishable vegetables like tomatoes, lettuce, and peppers, alongside seasonal fruits such as mangoes and citrus. Root crops like onions and carrots, while slightly more robust, also suffer significantly under high thermal stress. The local climate presents a severe challenge for these goods; during the peak dry season in April and May, temperatures frequently exceed 35°C and can spike above 40°C during increasingly common heatwaves. Because relative humidity remains low during this period, produce loses moisture rapidly, leading to shrivelling and a total loss of market value within days.

Traditional storage practices in Guinea-Bissau are often limited to keeping produce in shaded areas or under simple ventilated structures, which offer little protection against the extreme ambient heat. These methods are insufficient for modern food security needs, yet the high-tech alternatives typically found in industrial cold chains remain out of reach for most. Recent postharvest assessments in Guinea-Bissau (Defraeye et al., 2025) identified two main technological pathways for improving these conditions: low-cost passive evaporative cooling and small-scale active cooling. Passive systems, such as clay pot (or “Zeer pot”) coolers and charcoal cooling blankets, are inexpensive, locally manufacturable, and require no electricity. This makes them exceptionally well-suited to household or market stall use, particularly during the dry season when the air’s low humidity allows them to operate at peak efficiency.

In contrast, active systems, including thermoelectric boxes and domestic refrigerators, offer greater temperature control and more significant shelf-life extension. However, they require a stable energy supply, higher initial investment, and specialised maintenance capacity. These requirements are major barriers in Guinea-Bissau, which consists predominantly of rural areas with limited infrastructure. Given these constraints, there is a decisive and urgent need for energy-light, evaporative cooling solutions that can be deployed immediately at the community level to protect the hard-earned harvests of smallholder farmers.

Comparative Assessment and Selection of Cooling Technologies

Based on local resource assessments and cultural feasibility, clay pot coolers were selected for field testing over charcoal-based systems. While charcoal cooling blankets are technically effective, charcoal holds significant competing economic value as a primary cooking fuel in Guinea-Bissau. The risk that households would prioritise charcoal for daily heating rather than for cooling infrastructure made it a less viable option for long-term behavioral adoption. Consequently, the project focused on the “Zeer pot” design, leveraging the widespread availability of clay pots and existing local traditions of using ceramic vessels for water storage.

Laboratory Validation: Empa (St. Gallen, Switzerland)

Initial validation trials were conducted at the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology (Empa) to establish a performance baseline under controlled conditions.

- Specifications: The setup utilised two concentric clay pots with a 2-3 cm intermediate sand layer, kept saturated with water and sealed with a clay lid.

- Simulation: To simulate the thermal mass of a fully loaded unit, 5×0.5 L water bottles were placed inside the cooling chamber.

- Control Environment: Trials were held in a temperature-controlled indoor setting with average ambient temperatures of 21-23°C and relative humidity levels between 40-60%.

Field Implementation: Bafatá, Guinea-Bissau

Following laboratory success, field trials were executed in Bafatá during the 2025 dry season (January-February) to test performance in real-world tropical conditions.

- Local Adaptation: The design was modified to use locally available materials: plastic trays and standard clay pots typically used for drinking water.

- Construction: Sifted sand (with fine particles removed to improve capillary action) was filled into the plastic tray, and the clay pot was nested inside. The cooling effect was driven by moistening the sand with water and covering the unit with locally sourced burlap.

- Testing Environment: To replicate typical user behavior, the devices and an ambient reference box were placed in a shaded, well-ventilated vestibule of a residential house in Bafatá.

Performance Analysis

The efficiency of the clay pot cooler is driven by the physics of evaporative cooling, where the evaporation of water from the moist sand layer through the porous walls of the vessel extracts latent heat from the interior. Trials in Bafatá demonstrated that the interior of the clay pot maintains a temperature consistently 3-5°C lower than the ambient air. This cooling capacity is highly sensitive to atmospheric conditions, performing at its peak during the dry season when low relative humidity facilitates rapid evaporation. Conversely, during the rainy season when ambient humidity is high, the evaporation rate slows, leading to a less pronounced temperature reduction.

Beyond simple cooling, the system functions as a high-humidity chamber, maintaining internal relative humidity at approximately 95%. This saturated environment is crucial for horticultural preservation as it significantly reduces the vapour pressure deficit between the produce and the air. By preventing the fruits and vegetables from losing internal moisture, the system ensures that the produce does not shrivel, allowing it to retain its market weight and aesthetic appeal for a much longer period. Additionally, the mass of the clay and the water-saturated sand provides significant thermal inertia, which dampens extreme midday temperature spikes and protects the produce from the physiological stress caused by rapid heat fluctuations.

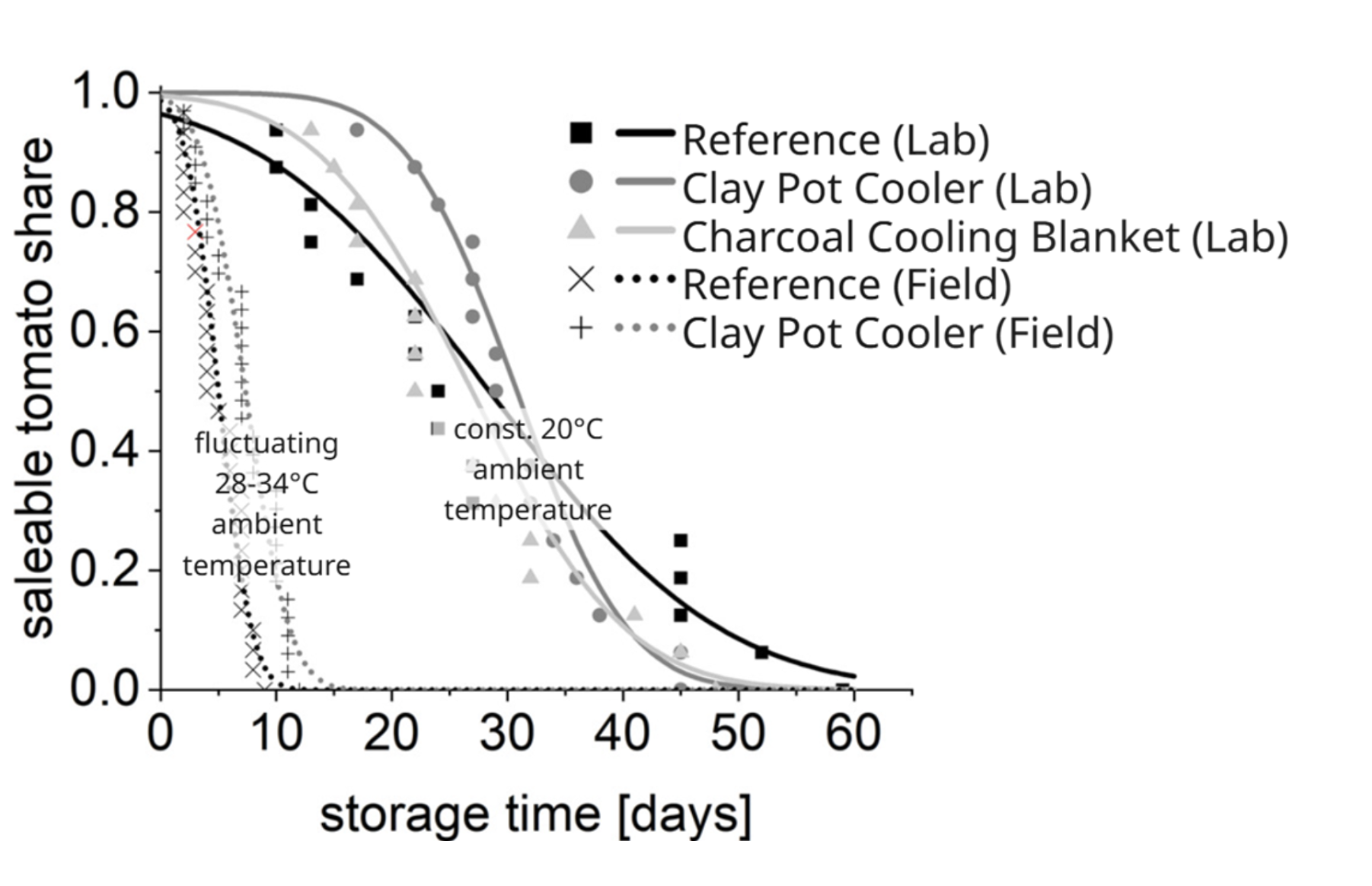

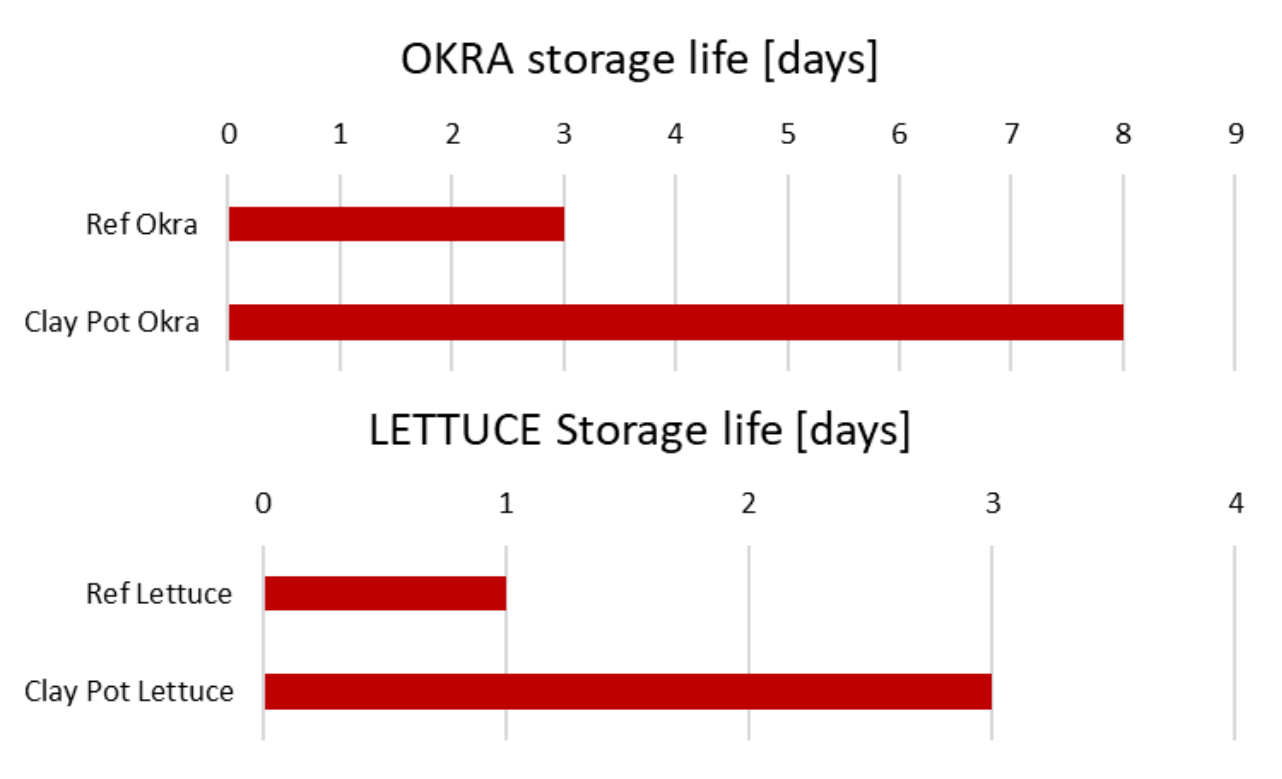

The integration of these thermal and hygroscopic effects leads to a measurable extension of shelf life across various horticultural products compared to traditional open-basket storage. For tomatoes, the trials indicated that a 50% increase in shelf life can be expected, providing farmers and market vendors with more days to secure a sale. The impact is even more pronounced for highly perishable greens and traditional staples; lettuce, which typically wilts within a single day, can be preserved for three days, while the storage life of okra is nearly tripled compared to an open basket.

Sourcing was relatively straightforward at most locations, as all necessary components were locally available and commonly used, though there were regional variations in material accessibility. Clay pots are traditionally utilised for storing drinking water, and plastic bins are part of everyday household activities, which significantly reduced costs and lowered the barriers to adoption. Once assembled, the clay pot coolers proved to be very easy to operate and required no specialised technical knowledge, making them highly accessible to users regardless of their level of formal education.

However, identifying an appropriate installation site proved more challenging than initially expected. Many potential locations were exposed to high levels of dust and intense direct sunlight, factors that compromised cooling performance and increased the need for frequent maintenance. Furthermore, the quality of the produce was already highly heterogeneous by the time it reached the storage stage due to varying pre-harvest conditions and handling practices. This initial variability limited the maximum achievable shelf-life extension and made it difficult to attribute quality changes solely to the cooling technology, highlighting the importance of integrating better harvesting practices alongside improved storage.

Community-led Validation

For the agricultural communities of Guinea-Bissau, the additional days provided by the clay pot cooler represent a critical economic buffer. By transforming a high-stakes race against spoilage into a manageable window for trade, this technology directly increases household revenue and reduces the volume of produce lost to decay.

To gauge community interest and willingness to adopt the solution, the BASE and Empa teams first conducted basic demonstrations on how to construct these coolers across the four target regions. This effort relied heavily on the support of a sister project under the FRSD, led by a consortium including SWISSAID, TOSTAN (Bafatá), COPE (Gabú), ADPP (Quinara), and OGD (Bolama). These partners had already been engaging with Farmer Clubs (cooperatives) to build capacity in agro-ecology, social cohesion, and entrepreneurship.

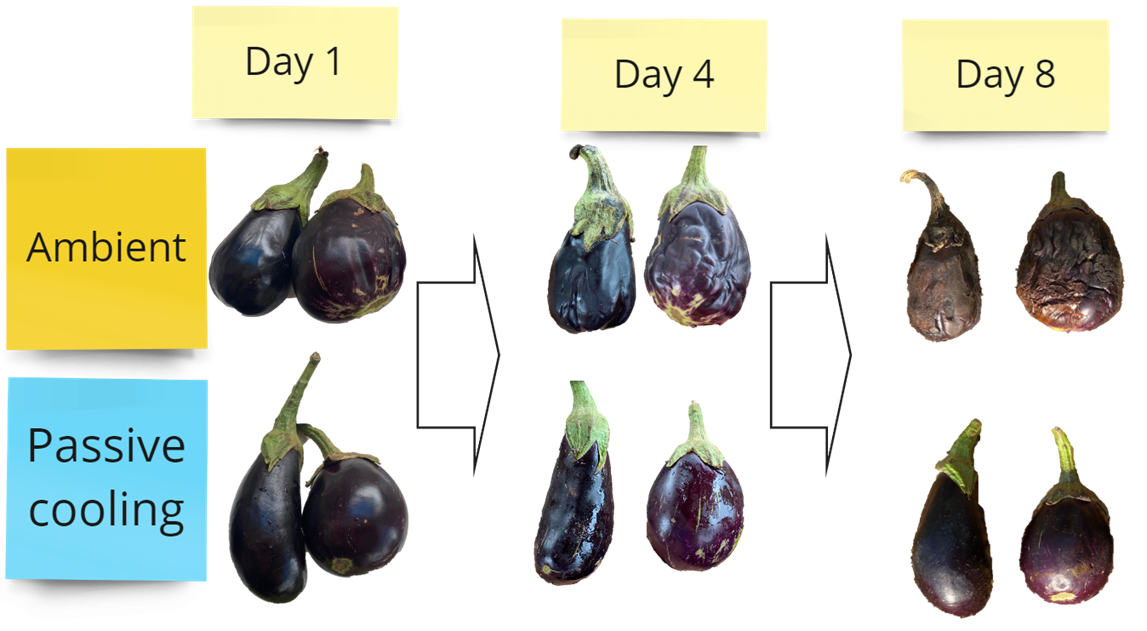

During these training sessions, the communities were not just shown how to assemble the structures; they were presented with a compelling live comparison. The teams displayed tomatoes and aubergines that had been transported across the country in a vehicle, half stored in a clay pot cooler and half in a traditional open basket. The difference was visible to the naked eye: while the produce in the open basket was wilting, bruised from travel, and showing clear signs of spoilage, the produce from the clay pot remained relatively plump and fresh.

To foster local ownership, each Farmer Club was invited to identify an Engineer of the Community; someone who enjoyed being around gadgets or just experimenting. This spontaneous selection nudged these individuals to take the lead on the technology, providing them with basic sensors to track the temperature differential inside and outside the pots and share the findings with their peers.

By putting the tools of validation directly into the hands of the farmers, the project moved beyond mere demonstration. This hands-on evidence struck a chord with the participants; seeing the data change in real-time provided the practical evidence needed to confirm that the coolers actually worked in their own environment. This confirmation of interest at the club level led BASE, Empa, and the consortium to formally include passive cooling in their broader training programs.

Scaling the Solution through Regional Training and Farmer Clubs

Over the course of 2025, BASE and Empa implemented a two-tier training program designed to move passive cooling from a concept to a widespread practice. This effort was supported by materials developed by CoolVeg, a leading non-profit organisation focused on technologies that utilise evaporative cooling for the preservation of fruits and vegetables in hot and dry climates.

The process began with 14 supervisors who received specialised post-harvest management and clay-pot cooler development training, delivered via Mundi Consulting. These supervisors then led four regional sessions in Bafatá, Gabú, Bolama, and Quinara, equipping 95 facilitators with the skills needed to train their communities.

Building on this momentum, our partner ADPP independently organised the replication of these trainings from facilitators directly to the Farmer Clubs. These sessions were deeply practical: every participant learned the importance of post-harvest care before building their own clay-pot cooler from scratch. To ensure the knowledge reached beyond project boundaries, seats were left open for community members outside the partner organisations, encouraging a natural, organic outreach.

In total, the training sessions with supervisors, facilitators, and the farmer clubs reached 580 people (406 women and 174 men).

Turning Challenges into a Roadmap for Adoption

While this community-level rollout proved the high demand for the technology, the transition from a training session to daily household use revealed several critical lessons. The most immediate hurdle was logistical: pot procurement. In regions like Quinara, many women were eager to adopt the coolers but found themselves stymied by a lack of local supply, with the nearest pots often located hours away in Oio or Bissau. This highlighted that even the most effective technology can only scale as fast as its local supply chain.

Environmental and biological factors also shaped the project’s evolution. The availability of clean water, essential for maintaining the moisture that drives the cooling effect, emerged as a vital prerequisite. Furthermore, the team had to manage expectations regarding the technology’s limits; for instance, while passive cooling is transformative for greens and tubers, it is unsuitable for onions, which are prone to fungal growth in moist environments. These practical realities underscored that success depends not just on the tool itself, but on its appropriate application within a specific climate and crop cycle.

Perhaps the most significant lesson was that behavioural change is a gradual journey. Even with high initial interest, the daily upkeep of a cooler is a commitment. Moving toward regular use requires local champions who continue to advocate for the technology based on their own success, supported by facilitators who are vital for answering the practical questions that inevitably arise on the go. Because the shift in habits is slow, success requires a persistent and an unrushed monitoring process. This approach allows teams to return frequently, listen to the specific difficulties faced by the community, and help tailor the technology to local needs—a task made easier by how simple, adaptable, and forgiving the clay-pot design is.

What Next?

To translate these lessons into long-term impact, the project will shift towards a more targeted strategy in its second phase, designed to overcome earlier logistical hurdles. By concentrating our efforts on eight select farmer clubs, we are prioritising regions where the essential infrastructure, specifically a reliable supply of clay pots, is already in place.

This approach ensures operational alignment by leveraging existing local resources, moving away from prescriptive models that often overlook the practicalities of the local landscape. By adopting this “feasibility-first” framework, we replace broad outreach with high-touch follow-ups and frequent monitoring. The project’s ultimate goal is to move beyond simple technology transfer, creating a sustainable, integrated cooling solution that moves from a temporary trial into a permanent economic buffer. By reducing post-harvest loss at the household level and allowing farmers to save crops for potential commercial sale, the project creates the market leverage needed for broader economic opportunities and subsequently contributes to increased food security across the region.